The Hexachord, Part 1

The Hexachord, Part 3

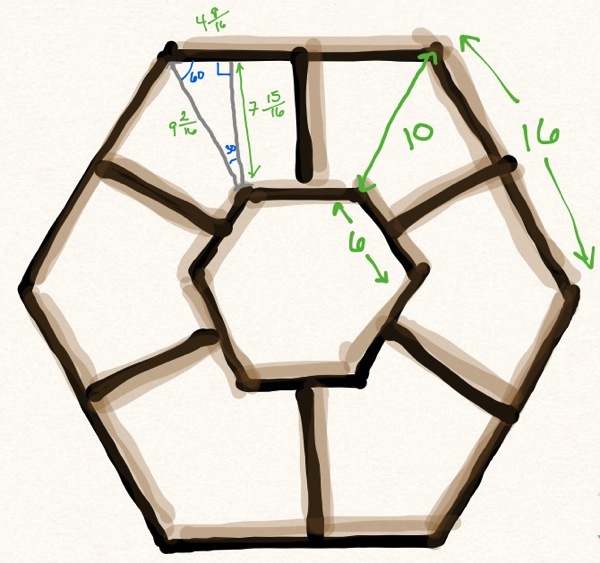

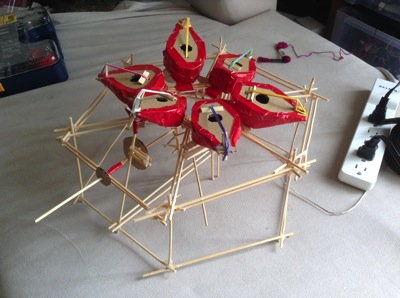

The Frame:

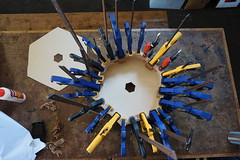

My Hexachord is built on a hexagonal frame, which I assembled with both glue and screws, cuz a heavy, three-foot-tall instrument is not something you want falling apart on you. Two frames are held six inches apart to allow room for the mechanisms that control the sound chambers, and an additional structure extends to hold the sound chambers.

I have learned just how much precision wood joinery requires (for the record: invest in good measuring tools). I have also discovered that CrashSpace members are all in love with the laser cutter (I know I will be too when I finally get around to using it), and everyone tells me how much easier it would be if I used it to make my mechanisms, or my sound chamber pieces, or… my lunch or something. In some ways, I’m sure it would, but sometimes I just want to get in there and use my hands. (Except for lunch. I’m a lousy cook.)

The Mechanisms:

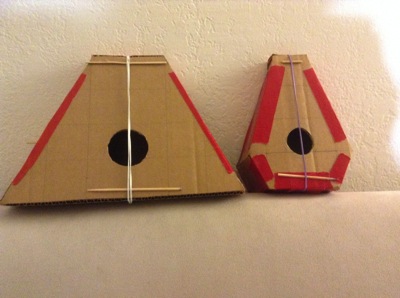

The hinges, like most everything else with the hexachord, are made of wood. There are two different kinds, a basic butt hinge, and a ball/socket hinge. I could have used pre-made metal butt hinges, but a) they would have stood out like a sore thumb amongst the lovely wood, and b) I am a glutton for punishment. The kind of ball and socket hinges I wanted would have been a bit harder to acquire pre-made, so I set about making my own custom ones.

|

|

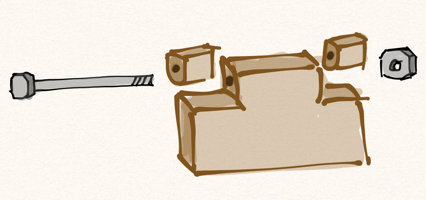

I used a scroll saw and drill press (two tools very frequently used in this project) to build the socket in multiple layers. The bottom and top layer have holes slightly smaller than the ball to give it an approximation of a complete socket. In the end it doesn’t need more than a few points of contact, and having the socket in contact over the whole ball would have applied a lot more friction than I wanted. The center is made of a square the same size as the top and bottom pieces, but with a hole a bit larger than the ball. I ultimately cut it into four pieces and used only two as spacers on opposite corners. The bottom piece was glued to the sound chamber, and the inside corner pieces were glued to that. The top piece I connected with screws in case I needed to remove/replace the sound chamber from the rest of the instrument. It’s a complicated thing; I like to leave myself the ability to repair.

There are nicely formed wooden spheres you can get, but finding just the right size wound up being more of a hassle than these wooden beads I tracked down at Michaels. I used a dremel to widen one hole to the right size for the dowel, and voila! A lovely, polished ball for the socket. The whole construction works rather well.

(Note: when using a power tool to widen an existing hole, don’t hold it with a finger over the other opening. Ow.)

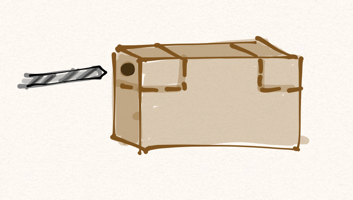

The butt hinge was easier, as there are folks who have done very fine tutorials (this one is gorgeous). If you drill the holes before cutting the side pieces, it’s much easier to get the pieces to line up properly. I bolted the cut pieces together, and then glued the flat side of the small ones to another block. Good, strong wood glue is important in something like this. I like Titebond. In future versions, I will probably use a glue more suited to musical instruments for the sound chambers, but it did the job pretty well here.

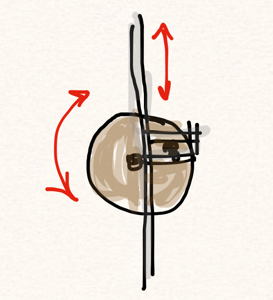

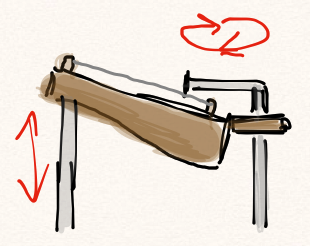

Finally, there was the matter of making use of these hinges. I wanted to be able to control the position of each sound chamber from the same side. No dancing around to make it work (though that could be fun too). As rotary motion is pretty easy to translate over long distances, I decided on using a knob for each sound chamber that connected to a scotch yoke mechanism. It’s very efficient for converting rotary motion to linear. There’s a disc and pegs, and ultimately several other smaller discs to hold stuff in place. It can get wriggly if you don’t take charge.

And those are the mechanisms. I expect I’ll make full Instructables for the construction of each sooner or later. Next time, the chaos of assembly, an interview, and videos!